Before this recital, Dr. Hoffman led one of the weekly composition symposia at CCM, and invited his son to perform Partenze for the composition students as a preview to the recital. I was there, as a DMA student at CCM at the time, and watched as Benjamin expertly played this work, as the older Hoffman beamed with pride. Following the performance both father and son took questions from the composition students about the work. One of my classmates asked Benjamin to compare the process of preparing a work by his father to that of a long-dead composer. Benjamin noted that while it was beneficiary to be able to work in person with his father, his preparation was not all that different. His reasoning was that performers should treat the work of living composers with the same respect and commitment as they would one by Bach, Beethoven, Brahms and the like.

Sadly, I did not have the foresight to record or write down Benjamin’s next statement, and I fear that recalling it years later will not do it its full justice, nevertheless it has stuck with me over the last five years, and was the impetus of this blog post. He argued that many probably feel that musical genius has gone out of the world. That the days of great works like those of Mozart, Beethoven, and others are over. Yet he contended that that was not the case. Composer-geniuses did still exist, and it was important to give their work just as much care as you would to those geniuses of the past. The implication here, of course, was that his father was one of those composer-geniuses.

I actually have no qualms in Benjamin Hoffman’s assessment of his father as a genius. In the little time I got to know him before his retirement, it was clear to me that Dr. Joel Hoffman was not only a talented composer and musician, but an incredibly intelligent and thoughtful individual. In fact, from the first moment I met him in my piano proficiency assessment, I was so intimidated by his knowledge and intensity, that I decided I would not study with him — perhaps, out of fear that he would see through my charade of calling myself a composer, and see me for the fraud I really and truly was. By the time I came to realize he was also a kind and supportive teacher, it was too late for me to study with him. He had announced his retirement.

I’m sure we can all admire Benjamin’s commitment to new music. A DMA candidate in violin at Yale, who studied from members of the Cincinnati Symphony as a child, Benjamin’s talent and dedication would make him a dream collaborator for many, especially those of us who have suffered through half-assed performances of our music by string players who would rather be working on Bach Partitas. Yet without knowing it, Benjamin was perpetuating a dangerous myth in not only art, but all of Western society: that great art and achievements can only be the product of genius. Such a myth is not only dangerous to those of us who write music — poisoning us with constant imposter syndrome and anxiety that our work will never be enough — but it has allowed musical culture to become ossified around the work of a select few composers – those worthy enough to be elevated to the status of genius. This ossification has turned concert and recital halls into museums, where music is not to be actively engaged with, but passively admired and respected by those cultured enough to appreciate it. Yet, what happens when society moves on from the museum? When people refuse to pay the high price of admission to listen to the music of long-dead white men? Who will be left to marvel at the works of these so-called geniuses?

Today, I am not here to disprove that composers of the Classical canon were geniuses. I have not searched dusty archives and found long-lost IQ tests taken by the likes of Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven. Rather, I am here to argue that the persistence of this label is not only unnecessary to the appreciation of the music of these individuals, but that doing away with this label is a step toward saving this art of notated concert music, which we are constantly told is in danger of being lost.

What is “Genius”?

But first, what is “genius?” We hold the concept of genius in extremely high esteem, yet the term is so ubiquitous that it has become essentially meaningless. While bemoaning the contemporary trend of over-exaggeration in mundane daily interactions, disgraced comedian Louis C.K. mused in his album Hilarious, “…all these words we use. Anybody can be a genius now. It used to be you had to have a thought no one ever had before, or you had to invent a number.” Yet now, he complained, an act as simple as getting an extra cup while eating out can earn the praise of, "Dude, you're a genius!"

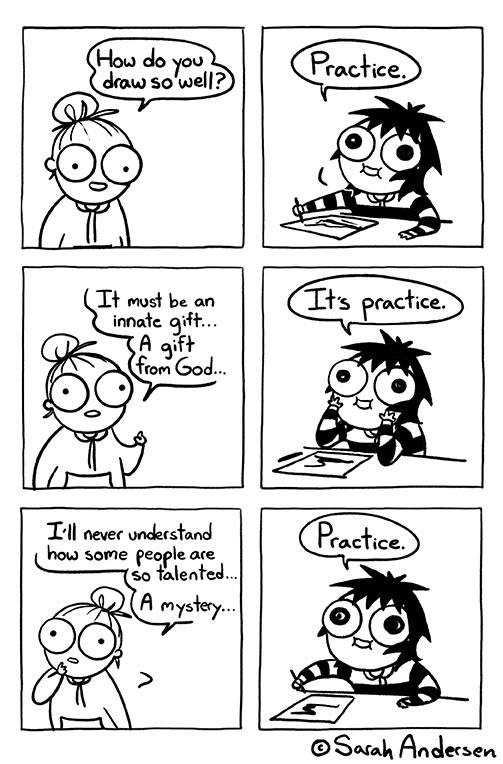

In her article, “Modernist Composers and the Concept of Genius,” musicologist Anna Piotrowska points to Enlightenment philosophers such as Kant for codifying genius in art. In his “Philosophy of Art,” within the larger Critique of Judgment, Kant himself writes, “Genius is the talent (natural endowment) which gives the rule to art. Since talent, as an innate productive faculty of the artist, belongs itself to nature, we may put it this way: Genius is the innate mental aptitude (ingenium) through which nature gives the rule to art.” It is interesting, and perhaps a little ironic, that the Age of Enlightenment — an era when philosophers strived for a greater emphasis on knowledge and reason, and when egalitarian ideals of equality helped to topple empires built upon unearned nobility — that such an era, would produce a concept that held an individual up as exceptional, not through study and practice, but because of some unearned innate ability.

In his book, The Possessor and the Possessed: Handel, Mozart, Beethoven, and the Idea of Musical Genius, musicologist Peter Kivy points even further back to Plato and Longinus, who imagined the genius to be in a state of possession by the muses who would use them as a conduit of creation. “Natural endowment,” possessed by muses — in these definitions we see genius as something that is gifted, not developed. Thinkers such as Cesare Lombroso would go even further, to connect genius to mental illness. This romanticism of mental illness is especially seen in discussions of Robert Schumann, who spent his dying days in a mental asylum. Genius was not only a possession, but it was a possession that the normal human mind could not always handle. It is not his training, years of focused work, or the propagation of his music by powerful patrons, publishers, and tastemakers that make the genius’s art great, it is the fact that he is chosen, gifted either by the divine or by nature to create the masterworks that we enjoy. And yes, I am purposefully using masculine pronouns to refer to the composer-genius, for reasons that will be made clear later (if they are not already painfully clear).

Both Piotrowska and Kivy point to the 18th and 19th Centuries has the height of the adoration of composer-geniuses. Names such as Handel, Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven appear as the usual suspects. These composers are known for their massive catalogues of works. The work of these men is so expansive and celebrated, that there is no surprise that the label of “genius” so easily applied. Handel wrote his most-beloved work, Messiah, in the span of twenty-four days (though he made numerous edits and revisions for years to come). Haydn was not only instrumental in defining the symphony as we know it, he wrote one hundred and four of them. Mozart was a well-known child-prodigy, who is said to have written the overture to Don Giovanni the day before (or perhaps even the day of) its premiere. Beethoven is not only credited with starting a new period of music, but composed some of his most celebrated music despite profound deafness. I wouldn’t dare to question the magnitude of these achievements, but the question at hand is: should we chalk these accomplishments up to genius which only few can achieve? Or, were they feats of skill which can be achieved by anyone who devotes their life to the craft?

Anna Piotrowski paints the picture of the revered composer-genius in her article. One whose necessary separation from society allowed them to not only create art for his own time, but to influence the future of music. It is perhaps through Beethoven that we get the fullest picture of the composer-genius. Of Beethoven, Piotrowski writes:

In musicological tradition, Beethoven is credited with the radical change in the status of composers. Even more than Mozart, Beethoven symbolised [sic] an emancipated composer independent of the court hierarchy; he denied the concept of a composer servant working for his master, often asked to undertake several jobs, sometimes unconnected with musicianship, or expected to perform on an instrument, conduct an orchestra, teach and finally compose.

She goes on to argue:

It was Beethoven who, in accordance with the tendency, dedicated himself mainly to instrumental music, which overtook the dominant role of vocal music; he composed instrumental music that gained almost sacral status in the eyes of early Romantic poets and intellectuals.

Already we can see flaws in this logic. Early in his career, Beethoven was employed as a musician in the court of the Elector of Bonn. He went on to have a number of royal patrons, including Archduke Rudolph Johann Joseph Rainier, who studied piano from Beethoven. Beethoven was a frequent performer and conductor who only stopped doing so once his deafness prevented it. And while Beethoven’s “absolute” instrumental music is greatly admired, so too are his works employing vocal forces. However, Piotrowski goes on to write:

Beethoven's patrons — mainly aristocratic ones — were not without ulterior motives: they managed to sustain their role as cultural leaders, who not only possessed good taste, but, while acting as real connoisseurs, could also still define the boundaries of what good, great music was and thus dictate what should be considered as fashionable and desirable — and what not. As a result of their attitude the image of the 'great composer' was being constructed at the same time. The process of creating the ideology of the 'great composer' began. The myth of a genius-artist was not born, as some authors pathetically write — it was socially constructed in order to support not the artists themselves, but their patrons.

We must ask ourselves who does the myth of the composer-genius serve and to what end? More importantly, we must ask if perpetuating the myth not only does a disservice to the work of these great composers, but if it is doing to harm our field. I humbly submit five points of argument as to why this myth is dangerous and should be abandoned:

- The myth of the composer-genius devalues the skill of the composer.

- The myth of genius paints composition as only a gift given to a chosen few.

- The myth of genius has been used to alienate the listener.

- The myth of genius is a tool to preserve the Classical canon, and has turned the concert hall into a museum.

- The myth of genius is used to keep music dead, white, and male.

This post is Part I in a two-part series. Points 1. and 2. will be covered in this post while points 3-5 will be covered in Part II.

The myth of the composer-genius devalues the skill of the composer.

In his famous book Outliers, author Malcolm Gladwell seeks to demystify the road to success for many exceptional individuals. While he contends that there are factors beyond our control that allow some to be more successful than others — such as when and where they are born, or their socio-economic status — no one achieves extreme success without sustained hard work. As evidence, he explores the work of psychologist K. Anders Ericsson, who in the 1990s surveyed students at the Academy of Music in Berlin. Ericsson found out that what set the highest achieving students apart from their colleagues was not God-given talent, but focused practice — about 10,000 hours of it. He goes on to quote neurologist Daniel Levitin:

In study after study, of composers, basketball players, fiction writers, ice skaters, concert pianists, chess players, master criminals, and what have you, this number comes up again and again. Of course, this doesn’t address why some people get more out of their practice sessions than others do. But no one has yet found a case in which true world-class expertise was accomplished in less time. It seems that it takes the brain this long to assimilate all that it needs to know to achieve true mastery.

He even looks at the career of our child-prodigy Mozart, who wrote his first music at six, and toured Europe playing in concert halls with his father and sister at age seven. He quotes psychologist Michael Howe:

…by the standards of mature composers, Mozart’s early works are not outstanding. The earliest pieces were all probably written down by his father, and perhaps improved in the process. Many of Wolfgang’s childhood compositions, such as the first seven of his concertos for piano and orchestra, are largely arrangements of works by other composers. Of those concertos that only contain music original to Mozart, the earliest that is now regarded as a masterwork (No. 9, K. 271) was not composed until he was twenty-one: by that time Mozart had already been composing concertos for ten years.

It must be noted that Ericsson would go on to challenge Gladwell’s use of the 10,000-hour rule, and that deciding which of Mozart’s pieces was his fist “masterwork” is a highly subjective endeavor. That said, it is not a controversial idea that it takes years of practice to master a skill. No one wakes up being able to compose concerti and symphonies. I would also argue that few would consider Mozart’s childhood and early adult works to be superior to his later works.

| As for Mozart’s skill as a child, well it helps when your father is Leopold Mozart, the pedagogue who literally wrote the book on violin performance: A Treatise on the Fundamental Principles of Violin Playing. Leopold would give keyboard lessons to his daughter, Marianne, and would later find a young Wolfgang imitating his big sister. Leopold transcribed, and no doubt edited the improvisations of the young Wolfgang that would become his first compositions. Mozart was no mere conduit, receiving his music from the beyond, he was a successful student of his father’s pedagogical methods. Returning to Beethoven, it is common to see his deafness often put forward as proof of his genius. Who, but a genius could still write such incredible music despite total hearing loss? And while it is an incredible feat to be admired, the answer is actually quite simple: aural skills. Beethoven’s hearing loss was gradual, not sudden. |

The act of composing is often treated as a mystery by both musicians and non-musicians. Many of us have had non-composers ask us about the process of writing, and remark how they could “never do that.” And while creativity can often be elusive, it can also be learned and honed. If that were not the case, there would be no reason to study composition, and the hundreds of composition departments in colleges and universities across the world would be wastes of money and space.

As an undergraduate composition student at Lawrence University in 2010, I was extremely excited that one of my compositional idols, the late David Maslanka would be in residency at the Conservatory. A year prior, I was considering quitting composition, and perhaps music altogether. However, it was performing A Child’s Garden of Dreams that inspired me not to give up. His influence on my output at that time is plainly evident, and I was honored to have been selected to have a lesson with him. Prior to my lesson, I was present at every rehearsal he sat in, and presentation he gave. With each presentation and interaction, I started to see his deep spiritual nature. In one presentation, instead of talking about his music, he led a group mediation. In another presentation, he stated that an important part of his artistry was allowing the music to speak through him. As someone who was in the process of discovering their own atheism, this was very disappointing to me. I wasn’t sure what I could learn from someone who received their inspiration from on high. Of course, I was relieved to find out in my lesson with him, that he had very concrete suggestions to give me concerning my music. He even gave me advice on getting more polished performances from my players upon hearing the lackluster recording of my piece.

While I don’t begrudge anyone their spiritual or religious beliefs, I truly believe that we must be open an honest about how we create and what inspires us. Our music is influenced by the work of those who have come before us. It is influenced by our environment and experiences. It is influenced by our training. If we insist on the act of creation as a mystical gift from the muses, we are diluting our own agency in that act of creation. If musical inspiration comes from above, why should we bother studying? Why should we bother with lessons? Why should we bother engaging with new ideas?

Composition requires skill and skill is learned, not given. If we choose to see the work of the great composers of the past as products of genius, or see these men as mere conduits for the divine art, then we are choosing to ignore their years of hard work, their years of struggle, and all of the teachers, mentors, friends, and loved ones who helped them achieve their greatness. If skill is given and not learned, that means that composition cannot be taught, that means that composers are chosen.

We often think of talent as innate. We see athletes, musicians, and thinkers who are able to accomplish amazing things, and assume that they are naturally disposed to that thing. But where does this innate talent come from? Who or what decides how talent is distributed? How are they chosen? One can only help but marvel at the logical dissonance between a capitalist society that values hard work, productivity, and merit-based achievement, and the idea that some members of that society are gifted with incredible talent that no one else could achieve.

Granted, for some talents, like athletic ability, natural factors such as height and bone structure help the athlete to excel at their sport. But what mental attributes make one pre-disposed to be a composer? Yes, we need to be comfortable spending long periods alone in solitude and concentrated work. We need to be able to create quickly and work on deadlines, but not only are we not born with these attributes, they can be learned.

If we believe that only certain individuals are given the “gift” of compositional skill, we send a dangerous message of exclusivity and privilege. Of course, this is the very message that was sent to a number of hopeful composers of the past, and helped maintain a homogenous club of male composers of European descent.

Part II discusses the role of the composer-genius myth in alienating the casual listener, preserving the Western cultural canon, and excluding non-male and non-white composers from that canon. Read on here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed