Since the 18th Century, Western Classical music has depended on the notion that its creators are geniuses: composers gifted with knowledge, insight, and ability not attainable by the average person. This has elevated their work to a near sacred status, imbuing their music with added meaning and relevance.

The myth of genius reached its height in the Romantic era, but if did not die with those composers. Not only are the works of these men still worshipped as genius, but the consequences of that worship still linger with us today. Through this two-part series, I submit five arguments for the abolishment of the myth of the composer-genius:

This post is Part II in a two-part series. Points 1. and 2. were covered in Part I while points 3-5 will be covered in here. Be sure to read Part I before reading on.

The myth of genius has been used to alienate the listener.

We are fascinated by genius. We marvel at brilliant minds. Truth be told, it is a point of pride that society venerates figures like Albert Einstein, Leonardo Da Vinci, or Benjamin Franklin. It says a lot about us that we flock to thinkers like Carl Sagan, Bill Nye, or Neil DeGrasse Tyson. We not only respect genius, we worship it. This fact was not lost on the composers of the 18th and 19th Centuries, or their promoters and patrons. In many ways, Classical music survives today because we still want to bear witness to that genius.

However, genius can also cause alienation. Not everyone wants to sit through a lecture that they do not understand. Neither is everyone interested in sitting in a stuffy concert hall for hours simply because some long-dead geniuses wrote the music that is being played. Often two solutions are given to this problem: either the listener must be educated in order to appreciate the genius of the music, or the ignorant listener is simply dismissed. It should be no surprise to us then, that our audiences remain homogenous in age, race, and socio-economic background.

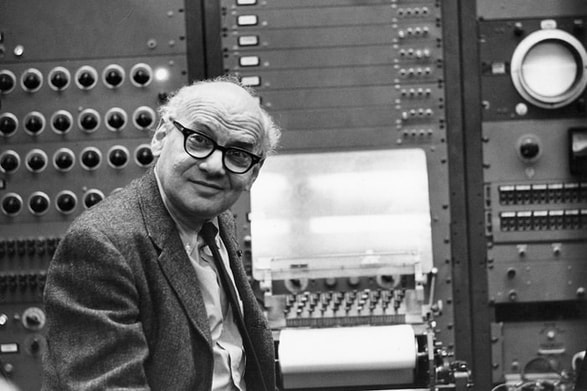

I would hope that few here are in favor of purposefully limiting our audiences to the elite. Our artform depends on public patronage, and our actions should seek to widen the audience, not narrow it further. Of course, an argument for a smaller and more elite audience was not so out of the ordinary in previous decades. In his infamous essay “Who Cares If You Listen” written for High Fidelity, Milton Babbitt argued that the isolation of the “composer-specialist” was to be embraced:

For I am concerned with stating an attitude towards the indisputable facts of the status and condition of the composer of what we will, for the moment, designate as "serious," "advanced," contemporary music. This composer expends an enormous amount of time and energy — and, usually, considerable money — on the creation of a commodity which has little, no, or negative commodity value. He is, in essence, a "vanity" composer. The general public is largely unaware of and uninterested in his music. The majority of performers shun it and resent it. Consequently, the music is little performed, and then primarily at poorly attended concerts before an audience consisting in the main of fellow 'professionals'. At best, the music would appear to be for, of, and by specialists.

Towards this condition of musical and societal "isolation," a variety of attitudes has been expressed, usually with the purpose of assigning blame, often to the music itself, occasionally to critics or performers, and very occasionally to the public. But to assign blame is to imply that this isolation is unnecessary and undesirable.

He goes on to say of the lay listener, who does not understand modern music:

Why should the layman be other than bored and puzzled by what he is unable to understand, music or anything else? It is only the translation of this boredom and puzzlement into resentment and denunciation that seems to me indefensible. After all, the public does have its own music, its ubiquitous music: music to eat by, to read by, to dance by, and to be impressed by. Why refuse to recognize the possibility that contemporary music has reached a stage long since attained by other forms of activity? The time has passed when the normally well-educated man without special preparation could understand the most advanced work in, for example, mathematics, philosophy, and physics. Advanced music, to the extent that it reflects the knowledge and originality of the informed composer, scarcely can be expected to appear more intelligible than these arts and sciences to the person whose musical education usually has been even less extensive than his background in other fields. But to this, a double standard is invoked, with the words “music is music," implying also that "music is just music." Why not, then, equate the activities of the radio repairman with those of the theoretical physicist, on the basis of the dictum that "physics is physics."

The myth of genius reached its height in the Romantic era, but if did not die with those composers. Not only are the works of these men still worshipped as genius, but the consequences of that worship still linger with us today. Through this two-part series, I submit five arguments for the abolishment of the myth of the composer-genius:

- The myth of the composer-genius devalues the skill of the composer.

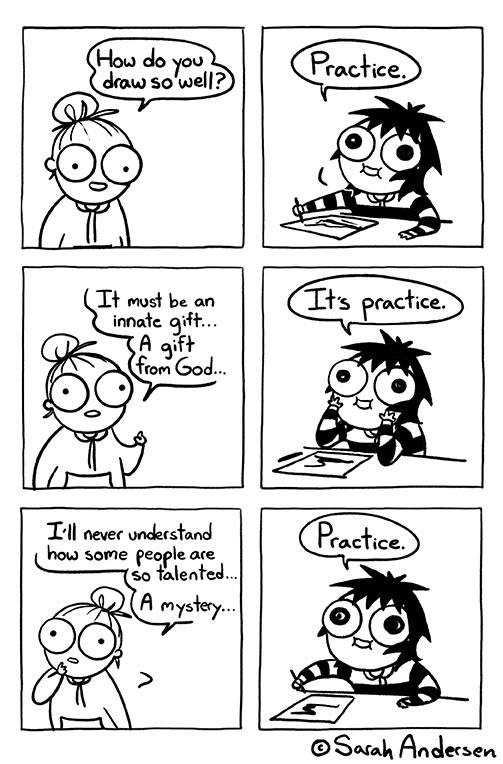

- The myth of genius paints composition as only a gift given to a chosen few.

- The myth of genius has been used to alienate the listener.

- The myth of genius is a tool to preserve the Classical canon, and has turned the concert hall into a museum.

- The myth of genius is used to keep music dead, white, and male.

This post is Part II in a two-part series. Points 1. and 2. were covered in Part I while points 3-5 will be covered in here. Be sure to read Part I before reading on.

The myth of genius has been used to alienate the listener.

We are fascinated by genius. We marvel at brilliant minds. Truth be told, it is a point of pride that society venerates figures like Albert Einstein, Leonardo Da Vinci, or Benjamin Franklin. It says a lot about us that we flock to thinkers like Carl Sagan, Bill Nye, or Neil DeGrasse Tyson. We not only respect genius, we worship it. This fact was not lost on the composers of the 18th and 19th Centuries, or their promoters and patrons. In many ways, Classical music survives today because we still want to bear witness to that genius.

However, genius can also cause alienation. Not everyone wants to sit through a lecture that they do not understand. Neither is everyone interested in sitting in a stuffy concert hall for hours simply because some long-dead geniuses wrote the music that is being played. Often two solutions are given to this problem: either the listener must be educated in order to appreciate the genius of the music, or the ignorant listener is simply dismissed. It should be no surprise to us then, that our audiences remain homogenous in age, race, and socio-economic background.

I would hope that few here are in favor of purposefully limiting our audiences to the elite. Our artform depends on public patronage, and our actions should seek to widen the audience, not narrow it further. Of course, an argument for a smaller and more elite audience was not so out of the ordinary in previous decades. In his infamous essay “Who Cares If You Listen” written for High Fidelity, Milton Babbitt argued that the isolation of the “composer-specialist” was to be embraced:

For I am concerned with stating an attitude towards the indisputable facts of the status and condition of the composer of what we will, for the moment, designate as "serious," "advanced," contemporary music. This composer expends an enormous amount of time and energy — and, usually, considerable money — on the creation of a commodity which has little, no, or negative commodity value. He is, in essence, a "vanity" composer. The general public is largely unaware of and uninterested in his music. The majority of performers shun it and resent it. Consequently, the music is little performed, and then primarily at poorly attended concerts before an audience consisting in the main of fellow 'professionals'. At best, the music would appear to be for, of, and by specialists.

Towards this condition of musical and societal "isolation," a variety of attitudes has been expressed, usually with the purpose of assigning blame, often to the music itself, occasionally to critics or performers, and very occasionally to the public. But to assign blame is to imply that this isolation is unnecessary and undesirable.

He goes on to say of the lay listener, who does not understand modern music:

Why should the layman be other than bored and puzzled by what he is unable to understand, music or anything else? It is only the translation of this boredom and puzzlement into resentment and denunciation that seems to me indefensible. After all, the public does have its own music, its ubiquitous music: music to eat by, to read by, to dance by, and to be impressed by. Why refuse to recognize the possibility that contemporary music has reached a stage long since attained by other forms of activity? The time has passed when the normally well-educated man without special preparation could understand the most advanced work in, for example, mathematics, philosophy, and physics. Advanced music, to the extent that it reflects the knowledge and originality of the informed composer, scarcely can be expected to appear more intelligible than these arts and sciences to the person whose musical education usually has been even less extensive than his background in other fields. But to this, a double standard is invoked, with the words “music is music," implying also that "music is just music." Why not, then, equate the activities of the radio repairman with those of the theoretical physicist, on the basis of the dictum that "physics is physics."

There was no need for Babbitt to even mention the word “genius.” His call for the embrace of isolation on the part of the “specialist,” and comparison of their work to that of a physicist, displays his thinking that concert music was no longer an artform to be enjoyed by the masses, but a scientific study. The patronage of the past was disappearing, and the public was not interested in supporting the creation of Modernist music, however, the academy was. Babbitt, who was instrumental in creating the first Ph.D program in composition at Princeton University — and who also studied and taught mathematics — saw his work as not only creation, but research. It is interesting to hear his argument for music as an almost scientific study, when unlike physics or biology, systems of music have little to do with natural phenomena. These systems — tonality and serialism — were not discovered, they were made up. Study of these systems do not yield deeper truths into nature or physics. Research and experimentation in music does not occur in a lab, they occur in the mind of the composer. Yet the academy became a natural safe space for this experimentation. Thus, began the continual quest to justify its existence with pseudo-scientific research and scholarship (but that is perhaps a rant for another day).

Of course, none of this is to criticize Modernism. Composers like Babbitt helped create new forms of expression, while also producing powerful and evocative music. Yet, that doesn’t make his words any less problematic. Babbitt famously opposed the title “Who Cares If You Listen,” given to the essay by an editor against his will, but that does not make his beliefs any less dangerous for the longevity of our artform. A self-satisfying artform created by specialists for the consumption of specialists alone is not sustainable. Why should the public, government, or university support an endeavor that is not meant to serve or be appreciated by anyone else but those who created it? A purely scientific approach to music is also foolhardy. An expressive and subjective artform turned into an objective study is no longer art.

While every listener will not be interested in Babbitt’s music, a wiser choice might have been to explain to the layman how his music is constructed, and why he chose to use the serial system instead of tonality. He could have explained that tonality only has the ability to express a portion of human emotions and psyche. He could have explained that even if the layman didn’t “understand” the music, perhaps there was still something in it for them to admire. After all, does the layman actually “understand” a Classical symphony or a work of modern art? Yet there is still something to be appreciated by exploring art that one does not understand. Instead, in 1958, Babbitt wasn’t concerned about reaching out to the layman. After all, if you’re a genius, why bother with the opinions of those beneath you?

The myth of genius is a tool to preserve the Classical canon, and has turned the concert hall into a museum.

While genius can be off-putting and alienating, genius can also command our fascination and admiration. We flock to hear great minds speak and impart some of their knowledge on us. The concert hall is where we flock to hear the voices of the great composers of the past. The act of creation is both mystifying and worshipped. We often feel like a part of the composer’s soul was left in a work, and hearing that music can reveal it. Going to a live performance is the closest we can come to communing with these long-dead geniuses. The concert hall is a temple, or perhaps a museum.

It has been millions of years since dinosaurs walked the planet. Thousands of years since the pharaohs of Egypt ruled. Hundreds of years since great artists like Da Vinci or Michelangelo created their legendary works of art. But in the museum, we can stand in the shadow of their remains, and somehow feel a little bit closer to them. This is what the concert hall has become over the centuries. It is sadly not out of the ordinary to see orchestral and chamber music seasons consisting solely of the music of the Common Practice. Each orchestra has to put their yearly “bold” stamp on the Beethoven, Brahms, or Mahler symphonic cycles. Occasionally a short new work will be sprinkled in here and there. Perhaps if we are lucky, we may get a full festival or series devoted to new works. Otherwise, Rite of Spring is the most radical that the orchestras of the United States and muster.

The concert hall is not a venue to see a living, breathing, and relevant artform in action. It is a museum to quietly appreciate the fossils of our artistic past. We (myself, very much included) go to hear music that we’ve heard dozens of time in concert, and hundreds of times in recordings, just to see how this conductor and orchestra do it differently from all the other conductors and orchestras in the world. In no other artform do you see such a strong grip to the works of the past. In most other artforms, new works are not merely tolerated, they are expected and celebrated. Art galleries across the country, from those in small towns to the most celebrated institutions of major cities, devote whole wings or even the whole building to new works. While aging patrons angrily storm out of modern music concerts, modern paintings sell for millions of dollars. While repertory theatres present the classics, new plays and musicals are constantly produced and celebrated. We do not go to movie theaters to watch the same classic films every year. Publishers do not merely keep reprinting and selling the same novels or poetry anthologies, they seek out the best and brightest new writers and extol their work. So why is concert music stuck in the 18th and 19th Centuries? Not only that, but why are American orchestras stuck in 18th and 19th Century Europe? A survey by the Baltimore Symphony of the 2014-15 seasons of twenty-one major orchestras showed that only 10.6% of works performed were by Americans. 37.8% were by German or Austrian composers, and 19.2% were by Russians. Only 11.4% of the repertoire were by living composers, and a measly 1.8% were by female composers. No data was offered on ethnicity.

In our service to dead European geniuses, we have neglected our own music. Some argue that modern music simply doesn’t sell. If orchestras are to continue to exist, then we must give the patrons what they want: more dead white men. However, we see orchestras such as the Los Angeles Philharmonic thrive while presenting innovative seasons with incredible gender and racial diversity without abandoning the classics. We must free ourselves from slavery from the canon and return our operatic and concert houses to what they were in the times of Mozart, Beethoven, and Haydn: cultural centers for the music of the current times.

The myth of genius is used to keep concert music dead, white, and male.

By turning the concert hall into a museum for the Classical canon, the myth of the composer-genius keeps concert music dead, white, and male. It is no secret the canon is almost wholly comprised of the work of European males. The occasional woman is sometimes included: Hildegard von Bingen, Francesca Caccini, Fanny Mendelssohn, Clara Schumann, Alma Mahler, and Amy Beach. Composers of color are mostly ignored. It is pretty clear that not all of the prerequisites for being a “genius” are skilled-based. White males are afforded the honor much easier than anyone else. Black composers such as Duke Ellington or Thelonious Monk are sometimes afforded the label of genius, however their work was mostly in Jazz. The effect of this exclusion of women and people of color from the pantheon of genius is obvious. Their work is not performed, heard, and valued at the same level of white men. After all, if we have the work of geniuses, why bother with anyone else?

That very argument was famously made in the pages of British magazine, The Spectator in the article, “There’s a good reason why there are no great female composers” by Damian Thompson. Mr. Thompson wrote this article not in 1715, 1815, or even 1915, but 2015. In it, he opposes calls to diversify the music education in Britain based on gender. His reasoning? He does not like the work of female composers compared to those of men. He says:

As I write this, I’m listening to a recording that couples the piano concertos of Mr and Mrs Schumann. In track three, I marvel yet again at Robert’s genius. The leaping melody of the finale turns into a fugue and then a waltz, enticed by the piano into modulations that never lose their power to surprise and delight.

Then comes track four, the first movement of Clara’s concerto, and within ten seconds we know it’s a dud. The first phrase is a platitude: nothing good can come of it and nothing does. Throughout, the virtuoso passagework is straight out of the catalogue. In her defence [sic], it’s an early piece; her mature Piano Trio is more accomplished, though its lyrical passages could have been cut and pasted from one of her husband’s works.

Mr. Thompson goes on to deride the work of Fanny Mendelssohn, Ethyl Smyth, and Amy Beach. While he admits that many of the barriers preventing women from pursuing composition are gone, the only living female composer he mentions is Judith Weir, current Master of the Queen’s Music. His only reasoning for disliking her work, is that her opera, Miss Fortune, received poor reviews. He does contend that, “There may be some [great female composers] in the future, though I’m not sure whether ‘greatness’ is achievable amid the messy eclecticism of 21st-century music.”

It is a mystery why Mr. Thompson, whose degrees are in religion and sociology, felt that his opinion was of any consequence to this subject. However, it does not take a degree to realize how foolish his argument is. One person’s musical tastes should not dictate whether or not any composer’s music should be studied. I may believe that the symphonies of Beethoven are vastly superior than those of Haydn, but I wouldn’t dare to question if Haydn should be studied in school. Even when he feels that Clara’s work matches that of her husband’s in the Piano Trio, he feels that is only more cause to ignore her, since its style is close to Robert’s. Throughout music history there are composers whose style emulated that of another composer, yet no one advocates for ignoring early Beethoven symphonies and piano sonatas because they harken to the style of Haydn.

But this is the problem with putting so much stock in the concept of genius. One listener’s genius is another listener’s derivative hack. And while most would scoff at Thompson’s outlandish beliefs, the repertoire lists of many of the ensembles, presenting organizations, recording labels, and music classrooms of the country would seem to demonstrate some silent agreement with the premise. These repertoire lists are filled with the music of Robert, Felix, and Gustav, but Clara, Fanny, and Alma are ignored. So too are great composers such as Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-George, Samuel Cooleridge-Taylor, William Grant Still, Florence Beatrice Price, Margaret Bonds, George Walker, and so many others (except perhaps for a token performance in the month of February).

Of course, none of this is to criticize Modernism. Composers like Babbitt helped create new forms of expression, while also producing powerful and evocative music. Yet, that doesn’t make his words any less problematic. Babbitt famously opposed the title “Who Cares If You Listen,” given to the essay by an editor against his will, but that does not make his beliefs any less dangerous for the longevity of our artform. A self-satisfying artform created by specialists for the consumption of specialists alone is not sustainable. Why should the public, government, or university support an endeavor that is not meant to serve or be appreciated by anyone else but those who created it? A purely scientific approach to music is also foolhardy. An expressive and subjective artform turned into an objective study is no longer art.

While every listener will not be interested in Babbitt’s music, a wiser choice might have been to explain to the layman how his music is constructed, and why he chose to use the serial system instead of tonality. He could have explained that tonality only has the ability to express a portion of human emotions and psyche. He could have explained that even if the layman didn’t “understand” the music, perhaps there was still something in it for them to admire. After all, does the layman actually “understand” a Classical symphony or a work of modern art? Yet there is still something to be appreciated by exploring art that one does not understand. Instead, in 1958, Babbitt wasn’t concerned about reaching out to the layman. After all, if you’re a genius, why bother with the opinions of those beneath you?

The myth of genius is a tool to preserve the Classical canon, and has turned the concert hall into a museum.

While genius can be off-putting and alienating, genius can also command our fascination and admiration. We flock to hear great minds speak and impart some of their knowledge on us. The concert hall is where we flock to hear the voices of the great composers of the past. The act of creation is both mystifying and worshipped. We often feel like a part of the composer’s soul was left in a work, and hearing that music can reveal it. Going to a live performance is the closest we can come to communing with these long-dead geniuses. The concert hall is a temple, or perhaps a museum.

It has been millions of years since dinosaurs walked the planet. Thousands of years since the pharaohs of Egypt ruled. Hundreds of years since great artists like Da Vinci or Michelangelo created their legendary works of art. But in the museum, we can stand in the shadow of their remains, and somehow feel a little bit closer to them. This is what the concert hall has become over the centuries. It is sadly not out of the ordinary to see orchestral and chamber music seasons consisting solely of the music of the Common Practice. Each orchestra has to put their yearly “bold” stamp on the Beethoven, Brahms, or Mahler symphonic cycles. Occasionally a short new work will be sprinkled in here and there. Perhaps if we are lucky, we may get a full festival or series devoted to new works. Otherwise, Rite of Spring is the most radical that the orchestras of the United States and muster.

The concert hall is not a venue to see a living, breathing, and relevant artform in action. It is a museum to quietly appreciate the fossils of our artistic past. We (myself, very much included) go to hear music that we’ve heard dozens of time in concert, and hundreds of times in recordings, just to see how this conductor and orchestra do it differently from all the other conductors and orchestras in the world. In no other artform do you see such a strong grip to the works of the past. In most other artforms, new works are not merely tolerated, they are expected and celebrated. Art galleries across the country, from those in small towns to the most celebrated institutions of major cities, devote whole wings or even the whole building to new works. While aging patrons angrily storm out of modern music concerts, modern paintings sell for millions of dollars. While repertory theatres present the classics, new plays and musicals are constantly produced and celebrated. We do not go to movie theaters to watch the same classic films every year. Publishers do not merely keep reprinting and selling the same novels or poetry anthologies, they seek out the best and brightest new writers and extol their work. So why is concert music stuck in the 18th and 19th Centuries? Not only that, but why are American orchestras stuck in 18th and 19th Century Europe? A survey by the Baltimore Symphony of the 2014-15 seasons of twenty-one major orchestras showed that only 10.6% of works performed were by Americans. 37.8% were by German or Austrian composers, and 19.2% were by Russians. Only 11.4% of the repertoire were by living composers, and a measly 1.8% were by female composers. No data was offered on ethnicity.

In our service to dead European geniuses, we have neglected our own music. Some argue that modern music simply doesn’t sell. If orchestras are to continue to exist, then we must give the patrons what they want: more dead white men. However, we see orchestras such as the Los Angeles Philharmonic thrive while presenting innovative seasons with incredible gender and racial diversity without abandoning the classics. We must free ourselves from slavery from the canon and return our operatic and concert houses to what they were in the times of Mozart, Beethoven, and Haydn: cultural centers for the music of the current times.

The myth of genius is used to keep concert music dead, white, and male.

By turning the concert hall into a museum for the Classical canon, the myth of the composer-genius keeps concert music dead, white, and male. It is no secret the canon is almost wholly comprised of the work of European males. The occasional woman is sometimes included: Hildegard von Bingen, Francesca Caccini, Fanny Mendelssohn, Clara Schumann, Alma Mahler, and Amy Beach. Composers of color are mostly ignored. It is pretty clear that not all of the prerequisites for being a “genius” are skilled-based. White males are afforded the honor much easier than anyone else. Black composers such as Duke Ellington or Thelonious Monk are sometimes afforded the label of genius, however their work was mostly in Jazz. The effect of this exclusion of women and people of color from the pantheon of genius is obvious. Their work is not performed, heard, and valued at the same level of white men. After all, if we have the work of geniuses, why bother with anyone else?

That very argument was famously made in the pages of British magazine, The Spectator in the article, “There’s a good reason why there are no great female composers” by Damian Thompson. Mr. Thompson wrote this article not in 1715, 1815, or even 1915, but 2015. In it, he opposes calls to diversify the music education in Britain based on gender. His reasoning? He does not like the work of female composers compared to those of men. He says:

As I write this, I’m listening to a recording that couples the piano concertos of Mr and Mrs Schumann. In track three, I marvel yet again at Robert’s genius. The leaping melody of the finale turns into a fugue and then a waltz, enticed by the piano into modulations that never lose their power to surprise and delight.

Then comes track four, the first movement of Clara’s concerto, and within ten seconds we know it’s a dud. The first phrase is a platitude: nothing good can come of it and nothing does. Throughout, the virtuoso passagework is straight out of the catalogue. In her defence [sic], it’s an early piece; her mature Piano Trio is more accomplished, though its lyrical passages could have been cut and pasted from one of her husband’s works.

Mr. Thompson goes on to deride the work of Fanny Mendelssohn, Ethyl Smyth, and Amy Beach. While he admits that many of the barriers preventing women from pursuing composition are gone, the only living female composer he mentions is Judith Weir, current Master of the Queen’s Music. His only reasoning for disliking her work, is that her opera, Miss Fortune, received poor reviews. He does contend that, “There may be some [great female composers] in the future, though I’m not sure whether ‘greatness’ is achievable amid the messy eclecticism of 21st-century music.”

It is a mystery why Mr. Thompson, whose degrees are in religion and sociology, felt that his opinion was of any consequence to this subject. However, it does not take a degree to realize how foolish his argument is. One person’s musical tastes should not dictate whether or not any composer’s music should be studied. I may believe that the symphonies of Beethoven are vastly superior than those of Haydn, but I wouldn’t dare to question if Haydn should be studied in school. Even when he feels that Clara’s work matches that of her husband’s in the Piano Trio, he feels that is only more cause to ignore her, since its style is close to Robert’s. Throughout music history there are composers whose style emulated that of another composer, yet no one advocates for ignoring early Beethoven symphonies and piano sonatas because they harken to the style of Haydn.

But this is the problem with putting so much stock in the concept of genius. One listener’s genius is another listener’s derivative hack. And while most would scoff at Thompson’s outlandish beliefs, the repertoire lists of many of the ensembles, presenting organizations, recording labels, and music classrooms of the country would seem to demonstrate some silent agreement with the premise. These repertoire lists are filled with the music of Robert, Felix, and Gustav, but Clara, Fanny, and Alma are ignored. So too are great composers such as Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-George, Samuel Cooleridge-Taylor, William Grant Still, Florence Beatrice Price, Margaret Bonds, George Walker, and so many others (except perhaps for a token performance in the month of February).

| Conclusion Perhaps then is time to put aside the myth of the composer-genius. This does not mean an abolition of the canon, but it may mean that perhaps we longer need to stack our performance seasons, albums, and music courses with the works of these dead white men. Perhaps Beethoven, Brahms, Tchaikovsky, and Mahler do not all need to be heard every season. Perhaps half or more of our programming could be dedicated to those forgotten by the canon or even better, living composers. Those works of the canon will not cease to exist if we do not play them year after year. We must reevaluate our relation to the canon, and shedding the weight of the composer-genius may be a first step in that reevaluation. At best, the Classical canon is a learning tool — a historical account of how concert music developed over the centuries. At worst, the canon can serve as a tool of patriarchal White supremacy, extoling the art of the Western “geniuses” over the musical heritage of native and minority cultures. The sooner we overcome our obsession with the canon, the sooner we can see the multitude of voices that could enrich the concert and recital halls. |

Now, more than ever, we must question if the concept of genius fits within the just society most of us hope to one day achieve. We must question if our morals are worth sacrificing for the sake of genius. Yes, Richard Wagner was a virulent anti-Semite (who borrowed heavily from the very Jewish composers he publicly insulted), but he was a genius! Yes, Carlo Gesualdo killed his wife and her lover in a jealous rage, and was found innocent due to his nobility, but he was a genius! Yes, Hector Berlioz stalked Harriet Smithson for years, and would later go on to be unfaithful to her in their marriage, but he was a genius who created his great Symphonie Fantastique for her! There is a reason why a very unstable and unintelligent president desperately wants to be seen as a “very stable genius.” Genius affords privileges not granted to common folk. Their work can live on despite their detestable views and actions, and it is up to us to “separate the art from the artist,” even when those detestable views are central to their art.

Yet our worship of genius has more personal costs as well. So many of us that write and perform music struggle with anxiety, depression, and feelings of inadequacy. We think that we are imposters and frauds who could never live up to work of the geniuses before us. We work ourselves to the bone striving to make each work a masterpiece. Instead we should realize the truth: the composers of the past were humans just like us. They had to put food on the table, pay the rent, and support their families. Not everything they wrote was a masterpiece, some just paid the bills.

We face many challenges in music, and shedding the weight of genius is certainly not going to fix them all, but maybe it is a starting point. Perhaps if we are able to separate ourselves from the myth of genius, then we will no longer see orchestral seasons with no works by living composers, women, or people of color. Perhaps the way we teach music will be more balanced and equitable. Perhaps our schools of music will be more diverse, both in its student and faculty bodies. Perhaps our audiences will be larger and more diverse. Perhaps we can dispense with the anxieties of imposter syndrome or masterpiece syndrome. Perhaps we can concentrate on the joy of making music.

Yet our worship of genius has more personal costs as well. So many of us that write and perform music struggle with anxiety, depression, and feelings of inadequacy. We think that we are imposters and frauds who could never live up to work of the geniuses before us. We work ourselves to the bone striving to make each work a masterpiece. Instead we should realize the truth: the composers of the past were humans just like us. They had to put food on the table, pay the rent, and support their families. Not everything they wrote was a masterpiece, some just paid the bills.

We face many challenges in music, and shedding the weight of genius is certainly not going to fix them all, but maybe it is a starting point. Perhaps if we are able to separate ourselves from the myth of genius, then we will no longer see orchestral seasons with no works by living composers, women, or people of color. Perhaps the way we teach music will be more balanced and equitable. Perhaps our schools of music will be more diverse, both in its student and faculty bodies. Perhaps our audiences will be larger and more diverse. Perhaps we can dispense with the anxieties of imposter syndrome or masterpiece syndrome. Perhaps we can concentrate on the joy of making music.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed